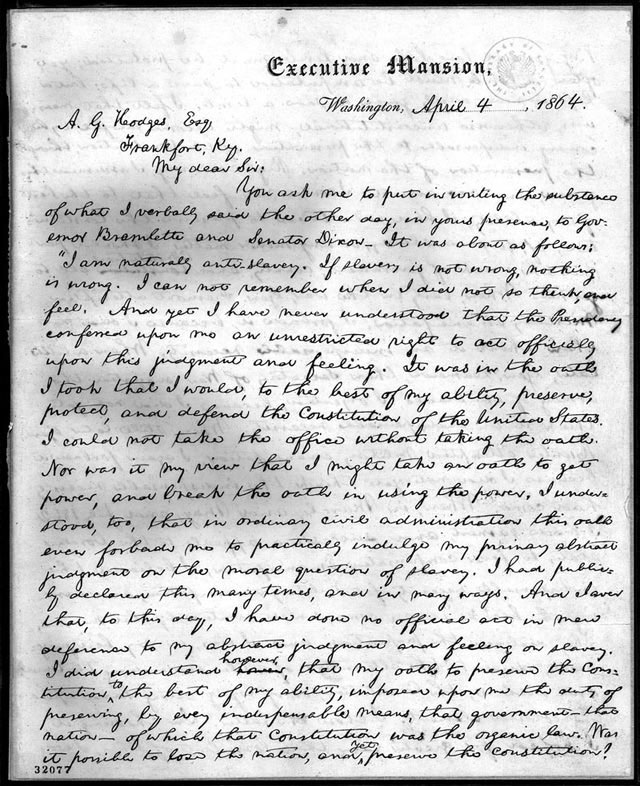

Letter to Albert Hodges (April 4, 1864)

|

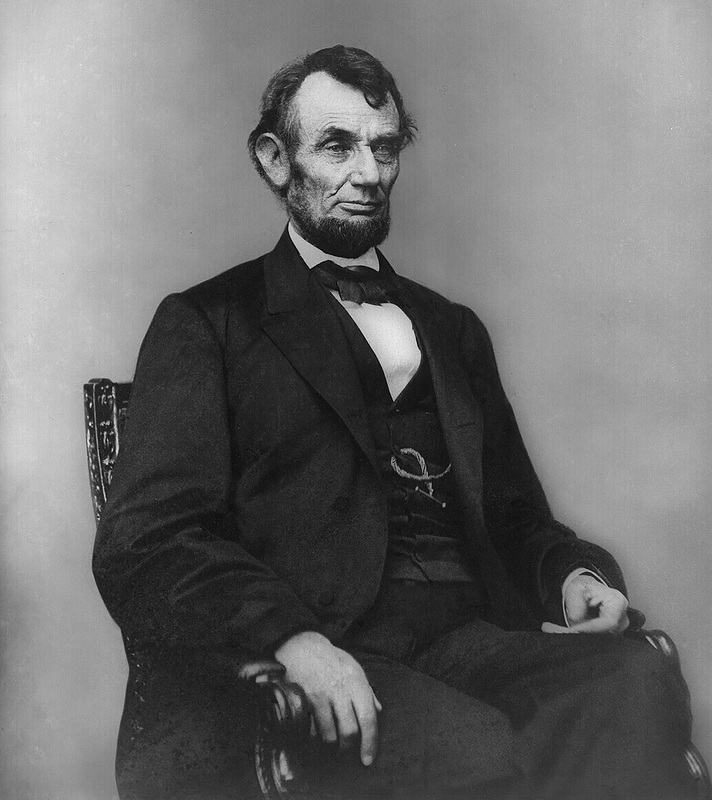

Mathew Brady Photographs of Civil War-Era Personalities and Scenes, National Archives and Records Administration (NARA)

|

A. G. Hodges, Esq Executive Mansion,

Frankfort, Ky. Washington, April 4, 1864.

My dear Sir: You ask me to put in writing the substance of what I verbally said the other day, in your presence, to Governor Bramlette and Senator Dixon. It was about as follows:

``I am naturally anti-slavery. If slavery is not wrong, nothing is wrong. I can not remember when I did not so think, and feel. And yet I have never understood that the Presidency conferred upon me an unrestricted right to act officially upon this judgment and feeling. It was in the oath I took that I would, to the best of my ability, preserve, protect, and defend the Constitution of the United States. I could not take the office without taking the oath. Nor was it my view that I might take an oath to get power, and break the oath in using the power. I understood, too, that in ordinary civil administration this oath even forbade me to practically indulge my primary abstract judgment on the moral question of slavery. I had publicly declared this many times, and in many ways. And I aver that, to this day, I have done no official act in mere deference to my abstract judgment and feeling on slavery. I did understand however, that my oath to preserve the constitution to the best of my ability, imposed upon me the duty of preserving, by every indispensable means, that government---that nation---of which that constitution was the organic law. Was it possible to lose the nation, and yet preserve the constitution? By general law life and limb must be protected; yet often a limb must be amputated to save a life; but a life is never wisely given to save a limb. I felt that measures, otherwise unconstitutional, might become lawful, by becoming indispensable to the preservation of the constitution, through the preservation of the nation. Right or wrong, I assumed this ground, and now avow it. I could not feel that, to the best of my ability, I had even tried to preserve the constitution, if, to save slavery, or any minor matter, I should permit the wreck of government, country, and Constitution all together. When, early in the war, Gen. Fremont attempted military emancipation, I forbade it, because I did not then think it an indispensable necessity. When a little later, Gen. Cameron, then Secretary of War, suggested the arming of the blacks, I objected, because I did not yet think it an indispensable necessity. When, still later, Gen. Hunter attempted military emancipation, I again forbade it, because I did not yet think the indispensable necessity had come. When, in March, and May, and July 1862 I made earnest, and successive appeals to the border states to favor compensated emancipation, I believed the indispensable necessity for military emancipation, and arming the blacks would come, unless averted by that measure. They declined the proposition; and I was, in my best judgment, driven to the alternative of either surrendering the Union, and with it, the Constitution, or of laying strong hand upon the colored element. I chose the latter. In choosing it, I hoped for greater gain than loss; but of this, I was not entirely confident. More than a year of trial now shows no loss by it in our foreign relations, none in our home popular sentiment, none in our white military force,---no loss by it any how or any ]where. On the contrary, it shows a gain of quite a hundred and thirty thousand soldiers, seamen, and laborers. These are palpable facts, about which, as facts, there can be no cavilling. We have the men; and we could not have had them without the measure.

[``]And now let any Union man who complains of the measure, test himself by writing down in one line that he is for subduing the rebellion by force of arms; and in the next, that he is for taking these hundred and thirty thousand men from the Union side, and placing them where they would be but for the measure he condemns. If he can not face his case so stated, it is only because he can not face the truth.['']

I add a word which was not in the verbal conversation. In telling this tale I attempt no compliment to my own sagacity. I claim not to have controlled events, but confess plainly that events have controlled me. Now, at the end of three years struggle the nation's condition is not what either party, or any man devised, or expected. God alone can claim it. Whither it is tending seems plain. If God now wills the removal of a great wrong, and wills also that we of the North as well as you of the South, shall pay fairly for our complicity in that wrong, impartial history will find therein new cause to attest and revere the justice and goodness of God. Yours truly

A. LINCOLN

Abraham Lincoln to Albert G. Hodges, April 4, 1864, Washington, DC, in Roy P. Basler, ed., The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln (8 vols., New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1953), 7: 281-283, http://quod.lib.umich.edu/l/lincoln/.

Frankfort, Ky. Washington, April 4, 1864.

My dear Sir: You ask me to put in writing the substance of what I verbally said the other day, in your presence, to Governor Bramlette and Senator Dixon. It was about as follows:

``I am naturally anti-slavery. If slavery is not wrong, nothing is wrong. I can not remember when I did not so think, and feel. And yet I have never understood that the Presidency conferred upon me an unrestricted right to act officially upon this judgment and feeling. It was in the oath I took that I would, to the best of my ability, preserve, protect, and defend the Constitution of the United States. I could not take the office without taking the oath. Nor was it my view that I might take an oath to get power, and break the oath in using the power. I understood, too, that in ordinary civil administration this oath even forbade me to practically indulge my primary abstract judgment on the moral question of slavery. I had publicly declared this many times, and in many ways. And I aver that, to this day, I have done no official act in mere deference to my abstract judgment and feeling on slavery. I did understand however, that my oath to preserve the constitution to the best of my ability, imposed upon me the duty of preserving, by every indispensable means, that government---that nation---of which that constitution was the organic law. Was it possible to lose the nation, and yet preserve the constitution? By general law life and limb must be protected; yet often a limb must be amputated to save a life; but a life is never wisely given to save a limb. I felt that measures, otherwise unconstitutional, might become lawful, by becoming indispensable to the preservation of the constitution, through the preservation of the nation. Right or wrong, I assumed this ground, and now avow it. I could not feel that, to the best of my ability, I had even tried to preserve the constitution, if, to save slavery, or any minor matter, I should permit the wreck of government, country, and Constitution all together. When, early in the war, Gen. Fremont attempted military emancipation, I forbade it, because I did not then think it an indispensable necessity. When a little later, Gen. Cameron, then Secretary of War, suggested the arming of the blacks, I objected, because I did not yet think it an indispensable necessity. When, still later, Gen. Hunter attempted military emancipation, I again forbade it, because I did not yet think the indispensable necessity had come. When, in March, and May, and July 1862 I made earnest, and successive appeals to the border states to favor compensated emancipation, I believed the indispensable necessity for military emancipation, and arming the blacks would come, unless averted by that measure. They declined the proposition; and I was, in my best judgment, driven to the alternative of either surrendering the Union, and with it, the Constitution, or of laying strong hand upon the colored element. I chose the latter. In choosing it, I hoped for greater gain than loss; but of this, I was not entirely confident. More than a year of trial now shows no loss by it in our foreign relations, none in our home popular sentiment, none in our white military force,---no loss by it any how or any ]where. On the contrary, it shows a gain of quite a hundred and thirty thousand soldiers, seamen, and laborers. These are palpable facts, about which, as facts, there can be no cavilling. We have the men; and we could not have had them without the measure.

[``]And now let any Union man who complains of the measure, test himself by writing down in one line that he is for subduing the rebellion by force of arms; and in the next, that he is for taking these hundred and thirty thousand men from the Union side, and placing them where they would be but for the measure he condemns. If he can not face his case so stated, it is only because he can not face the truth.['']

I add a word which was not in the verbal conversation. In telling this tale I attempt no compliment to my own sagacity. I claim not to have controlled events, but confess plainly that events have controlled me. Now, at the end of three years struggle the nation's condition is not what either party, or any man devised, or expected. God alone can claim it. Whither it is tending seems plain. If God now wills the removal of a great wrong, and wills also that we of the North as well as you of the South, shall pay fairly for our complicity in that wrong, impartial history will find therein new cause to attest and revere the justice and goodness of God. Yours truly

A. LINCOLN

Abraham Lincoln to Albert G. Hodges, April 4, 1864, Washington, DC, in Roy P. Basler, ed., The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln (8 vols., New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1953), 7: 281-283, http://quod.lib.umich.edu/l/lincoln/.

Lindsay Peterson, Lincoln's Public Letter to A.G. Hodges, podcast audio, July 27, 2016,

https://soundcloud.com/user-767385208/lincoln-public-letter-to-a-g

https://soundcloud.com/user-767385208/lincoln-public-letter-to-a-g

Searchable Text:

On April 4, 1864, Lincoln wrote a public letter to Albert Hodges, a newspaper editor from Kentucky. Kentucky was a Unionist slave state and worried about Lincoln’s emancipation and civil liberties policies. Lincoln had previously met with Hodges, along with leading Kentucky politicians, and Hodges asked Lincoln to follow up their conversation with a written account of their discussion on the subject of emancipation. The letter described the evolution of Lincoln’s emancipation policy with the goal being to convince Kentuckians of the necessity of his actions in preparation for the upcoming election. As a border state, Kentucky, recognized that the 1864 presidential election would address the future of slavery in their own state and the country and were therefore, skeptical of, but eager to understand Lincoln’s actions. Through the direct, yet personal, use of a public letter, Lincoln employed the rhetorical device of negation, used relatable comparisons, addressed the skepticism of his audience, and connected to religion in his best attempt to convince the Kentucky public of the “indispensable necessity” of emancipation.

Lincoln used public letters during his presidency to “rally opinion” for his policies.[1] His other public letters included a letter to Horace Greeley in August 1862 and to James Conkling in August 1863, both on the subject of emancipation. As Historian Ronald White noted, in this letter Lincoln needed the people to understand “both the vision and the restraints that had guided him.”[2] Hence, Lincoln’s letter described not only what he did, but why he did it. White noted when “people listened to Lincoln speak, they learned to trust him;” [3] Lincoln tried to accomplish the same outcome with his public letters. The public letters offered Lincoln the opportunity to reach people in a format more personal than a speech – because a letter is addressed to an individual and meant to be read in the comfort of one’s home, as compared to a speech, Lincoln tried to achieve the sentiment of a one-on-one interaction. While the letter was addressed to Hodges, Lincoln intended it to be public letter and can be read in this way. In response to his use of public letters, The New York Times in 1863 wrote that through this method Lincoln “invariably gets at the needed truth of the time.”[4]

In describing the evolution of his policy, Lincoln first stated his personal views before noting his public duties. Lincoln opened his letter with “I am naturally anti-slavery. If slavery is not wrong, nothing is wrong. I can not remember when I did not so think, and feel.”[5] By beginning with his personal views, Lincoln humanized himself by being straightforward with the people of Kentucky in acknowledging that he is a person with his own views in addition to being the president. As Lincoln transitioned into discussing his public duties, he repeatedly referred to the oath of office – a responsibility he respected deeply. In recognizing the distinction between his personal views and public duties, Lincoln stated, “I have never understood that the Presidency conferred upon me an unrestricted right to act officially upon this judgment and feeling….And I aver that, to this day, I have done no official act in mere deference to my abstract judgment and feeling on slavery.” His “judgment and feeling” referred to his earlier statement that “If slavery is not wrong, nothing is wrong.” Lincoln wanted the reader to understand that he recognized the limits of his public duty – and that he did not let his personal views dictate his political decisions.

As Lincoln discussed his public duties, he utilized his “rhetorical ‘signature’” – the negative – to try to convince the public. Writing, “It was in the oath I took that I would, to the best of my ability, preserve, protect, and defend the Constitution of the United States. I could not take the office without taking the oath.”[6] The negative is seen in Lincoln’s sentence construction – by phrasing his ideas in the context of not taking office, instead of in a positive construction. In “Lincoln’s Rhetoric,” Historian Douglas Wilson noted that people are “moralized by the negative” and the strategy is “employed to emphasize restraint.”[7] Lincoln’s rhetorical use of the negative in his opening sentences set the stage for the underlying moral elements of his position. Lincoln continued in his writing to show restraint, writing “Nor was it my view that I might take an oath to get power, and break the oath in using the power.”[8] Lincoln subsequently recounted the restraint he showed in regards to emancipation earlier in the war.[9] Even though people did not necessarily realize what Lincoln was doing here with his subtle use of language, the negation helped set the reader up to understand his policy.

In the middle of his letter, Lincoln compared the emancipation debate to “life and limb.” Lincoln questioned, “Was it possible to lose the nation and yet preserve the constitution?”[10] He related this to the fact that “a limb must be amputated to save a life; but a life is never wisely given to save a limb.”[11] The life, representing the union, must be protected even if it means sacrificing the limb, the Constitution. Like a surgeon, Lincoln waited until the last minute to perform this “amputation.” Amputation implied pain and suffering and would be all too familiar to a citizenry dealing with the Civil War; in this, Lincoln acknowledged that he knew this was a tough decision, but that he hoped the people would understand its necessity. This stark comparison also provides insight into Lincoln’s understanding of how he came to be formally supporting emancipation. As a president constantly being confronted by staggering death tolls, Lincoln would have been doing everything in his power to save lives – both literally on the battlefield, and figuratively in his comparison to maintaining the union and Constitution. The imagery Lincoln created through his comparison was part of his strategy to convince the public.

After making this comparison, Lincoln acknowledged those who doubted his constitutional power to emancipate the slaves, writing, “I felt that measures, otherwise unconstitutional, might become lawful, by becoming indispensable to the preservation of the constitution, through the preservation of the nation. Right or wrong, I assumed this ground, and now avow it. I could not feel that, to the best of my ability, I had even tried to preserve the constitution if, to save slavery, or any minor matter.” Again, he humanized himself to his audience in recognizing that some might not agree with him, but stating that he felt it was his duty to emancipate the slaves in order to uphold his oath of office. However, as Lincoln noted, he did not allow emancipation before it was essential – evidenced by the fact that he “forbade” earlier emancipation attempts by General Fremont, Cameron, and Hunter.[12] Lincoln recalled, “When, in March, and May, and July 1862 I made earnest, and successive appeals to the border states to favor compensated emancipation, I believed the indispensable necessity for military emancipation, and arming the blacks would come, unless averted by that measure. They declined the proposition; and I was, in my best judgment, driven to the alternative of either surrendering the Union, and with it, the Constitution, or of laying strong hand upon the colored element. I chose the latter.”[13] It is important to note that before the war, Lincoln and the Republicans were always advocating for the containment of slavery with the eventual voluntary abolition of slavery by the slave states. They were not advocating for the federal government to abolish slavery where it already existed. Here, Lincoln is looking to get the border states to adopt a gradual emancipation plan with compensation. When this offer is declined, he finally believed in the “indispensable necessity” of military emancipation.[14] So, slavery would have to end for military reasons.

Lincoln ended his letter using religion to further connect to his audience. It is interesting to note that this ending was not part of the original conversation with Hodges; it is possible that Lincoln did not find it vital in his conversation with the prominent men but saw its potential with the regular citizens. Lincoln wrote, “In telling this tale I attempt no compliment to my own sagacity. I claim not to have controlled events, but confess plainly that events have controlled me. Now, at the end of three years struggle the nation’s condition is not what either party, or any man devised, or expected. God alone can claim it.”[15] In closing in this manner, he pivoted the responsibility for his choices from himself to a “Divine purpose…at work.” [16] This is a similar theme to Lincoln’s Second Inaugural Address that he gave in March 1865 after winning reelection in November 1864. As Historian David Herbert Donald noted, “This comforting doctrine allowed the President to live with himself by shifting some of the responsibility for all the suffering.”[17] So, even if the reader did not trust Lincoln based on his personal beliefs, the reader could trust that Lincoln’s decision was in part guided by God.

Lincoln’s ultimate goal with this letter was to explain the evolution of his emancipation policy and convince the people of Kentucky in the process. Hodges wrote to Lincoln on April 22, after this public letter, saying, “It is with feelings of profound satisfaction I inform you, that… I have been receiving information of your steady gain upon the gratitude and confidence of the People of Kentucky.”[18] Yet, in the November election, Kentucky was one of only three states to vote for Democrat George McClellan.[19] However, this should not be viewed as a failure for Lincoln, as Kentuckians supported Lincoln more in 1864 than they had in 1860.[20] It is possible that his April 4, 1864, public letter to Albert Hodges convinced people to trust him in claiming the “indispensable necessity” of emancipation. More broadly the letter provided insight into Lincoln’s own understanding of the evolution of his emancipation policies.

[1] Ronald White, Lincoln’s Greatest Speech: The Second Inaugural, (New York: Simon and Schuster, 2006), 82, https://books.google.com/books?id=wtfLtP2LhCcC&printsec=frontcover&source=gbs_ge_summary_r&cad=0#v=onepage&q&f=false.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Douglas L. Wilson, “Lincoln’s Rhetoric,” Journal of the Abraham Lincoln Association, 34, 1, (2013), http://hdl.handle.net/2027/spo.2629860.0034.103.

[5] Abraham Lincoln to Albert G. Hodges, April 4, 1864, Washington, DC, in Roy P. Basler, ed., The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln (8 vols., New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1953), 7: 281-283, http://quod.lib.umich.edu/l/lincoln/.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Wilson, “Lincoln’s Rhetoric.”

[8] Abraham Lincoln to Albert G. Hodges, April 4, 1864.

[9] Wilson, “Lincoln’s Rhetoric.”

[10] Abraham Lincoln to Albert G. Hodges, April 4, 1864.

[11] Ibid.

[12] Ibid.

[13] Ibid.

[14] Ibid.

[15] Ibid.

[16] David Herbert Donald, Lincoln (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1995), 514-515, from: http://housedivided.dickinson.edu/sites/lincoln/letter-to-albert-hodges-april-4-1864/.

[17] Ibid.

[18] Albert G. Hodges to Abraham Lincoln, April 22, 1864, Letter, From Library of Congress, The Abraham Lincoln Papers.

http://memory.loc.gov/cgi-bin/query/r?ammem/mal:@field(DOCID+@lit(d3254000)) (accessed July 20, 2016).

[19] David Leip, 1864 Presidential General Election Results – Kentucky, U.S. Election Atlas, Accessed July 20, 2016, “http://uselectionatlas.org/RESULTS/state.php?f=0&fips=21&year=1864.

[20] “Kentucky’s Abraham Lincoln,” The Kentucky Historical Society, Accessed July 20, 2016, http://www.lrc.ky.gov/record/Moments09RS/web/Lincoln%20moments%2025.pdf.

While this difference can also be attributed to the mid-war political reality in Kentucky (where many Kentuckians were fighting for the Confederacy) and the fact that Kentucky was military occupied, some of the support might be tied to this public letter in which Lincoln explained his policies.

On April 4, 1864, Lincoln wrote a public letter to Albert Hodges, a newspaper editor from Kentucky. Kentucky was a Unionist slave state and worried about Lincoln’s emancipation and civil liberties policies. Lincoln had previously met with Hodges, along with leading Kentucky politicians, and Hodges asked Lincoln to follow up their conversation with a written account of their discussion on the subject of emancipation. The letter described the evolution of Lincoln’s emancipation policy with the goal being to convince Kentuckians of the necessity of his actions in preparation for the upcoming election. As a border state, Kentucky, recognized that the 1864 presidential election would address the future of slavery in their own state and the country and were therefore, skeptical of, but eager to understand Lincoln’s actions. Through the direct, yet personal, use of a public letter, Lincoln employed the rhetorical device of negation, used relatable comparisons, addressed the skepticism of his audience, and connected to religion in his best attempt to convince the Kentucky public of the “indispensable necessity” of emancipation.

Lincoln used public letters during his presidency to “rally opinion” for his policies.[1] His other public letters included a letter to Horace Greeley in August 1862 and to James Conkling in August 1863, both on the subject of emancipation. As Historian Ronald White noted, in this letter Lincoln needed the people to understand “both the vision and the restraints that had guided him.”[2] Hence, Lincoln’s letter described not only what he did, but why he did it. White noted when “people listened to Lincoln speak, they learned to trust him;” [3] Lincoln tried to accomplish the same outcome with his public letters. The public letters offered Lincoln the opportunity to reach people in a format more personal than a speech – because a letter is addressed to an individual and meant to be read in the comfort of one’s home, as compared to a speech, Lincoln tried to achieve the sentiment of a one-on-one interaction. While the letter was addressed to Hodges, Lincoln intended it to be public letter and can be read in this way. In response to his use of public letters, The New York Times in 1863 wrote that through this method Lincoln “invariably gets at the needed truth of the time.”[4]

In describing the evolution of his policy, Lincoln first stated his personal views before noting his public duties. Lincoln opened his letter with “I am naturally anti-slavery. If slavery is not wrong, nothing is wrong. I can not remember when I did not so think, and feel.”[5] By beginning with his personal views, Lincoln humanized himself by being straightforward with the people of Kentucky in acknowledging that he is a person with his own views in addition to being the president. As Lincoln transitioned into discussing his public duties, he repeatedly referred to the oath of office – a responsibility he respected deeply. In recognizing the distinction between his personal views and public duties, Lincoln stated, “I have never understood that the Presidency conferred upon me an unrestricted right to act officially upon this judgment and feeling….And I aver that, to this day, I have done no official act in mere deference to my abstract judgment and feeling on slavery.” His “judgment and feeling” referred to his earlier statement that “If slavery is not wrong, nothing is wrong.” Lincoln wanted the reader to understand that he recognized the limits of his public duty – and that he did not let his personal views dictate his political decisions.

As Lincoln discussed his public duties, he utilized his “rhetorical ‘signature’” – the negative – to try to convince the public. Writing, “It was in the oath I took that I would, to the best of my ability, preserve, protect, and defend the Constitution of the United States. I could not take the office without taking the oath.”[6] The negative is seen in Lincoln’s sentence construction – by phrasing his ideas in the context of not taking office, instead of in a positive construction. In “Lincoln’s Rhetoric,” Historian Douglas Wilson noted that people are “moralized by the negative” and the strategy is “employed to emphasize restraint.”[7] Lincoln’s rhetorical use of the negative in his opening sentences set the stage for the underlying moral elements of his position. Lincoln continued in his writing to show restraint, writing “Nor was it my view that I might take an oath to get power, and break the oath in using the power.”[8] Lincoln subsequently recounted the restraint he showed in regards to emancipation earlier in the war.[9] Even though people did not necessarily realize what Lincoln was doing here with his subtle use of language, the negation helped set the reader up to understand his policy.

In the middle of his letter, Lincoln compared the emancipation debate to “life and limb.” Lincoln questioned, “Was it possible to lose the nation and yet preserve the constitution?”[10] He related this to the fact that “a limb must be amputated to save a life; but a life is never wisely given to save a limb.”[11] The life, representing the union, must be protected even if it means sacrificing the limb, the Constitution. Like a surgeon, Lincoln waited until the last minute to perform this “amputation.” Amputation implied pain and suffering and would be all too familiar to a citizenry dealing with the Civil War; in this, Lincoln acknowledged that he knew this was a tough decision, but that he hoped the people would understand its necessity. This stark comparison also provides insight into Lincoln’s understanding of how he came to be formally supporting emancipation. As a president constantly being confronted by staggering death tolls, Lincoln would have been doing everything in his power to save lives – both literally on the battlefield, and figuratively in his comparison to maintaining the union and Constitution. The imagery Lincoln created through his comparison was part of his strategy to convince the public.

After making this comparison, Lincoln acknowledged those who doubted his constitutional power to emancipate the slaves, writing, “I felt that measures, otherwise unconstitutional, might become lawful, by becoming indispensable to the preservation of the constitution, through the preservation of the nation. Right or wrong, I assumed this ground, and now avow it. I could not feel that, to the best of my ability, I had even tried to preserve the constitution if, to save slavery, or any minor matter.” Again, he humanized himself to his audience in recognizing that some might not agree with him, but stating that he felt it was his duty to emancipate the slaves in order to uphold his oath of office. However, as Lincoln noted, he did not allow emancipation before it was essential – evidenced by the fact that he “forbade” earlier emancipation attempts by General Fremont, Cameron, and Hunter.[12] Lincoln recalled, “When, in March, and May, and July 1862 I made earnest, and successive appeals to the border states to favor compensated emancipation, I believed the indispensable necessity for military emancipation, and arming the blacks would come, unless averted by that measure. They declined the proposition; and I was, in my best judgment, driven to the alternative of either surrendering the Union, and with it, the Constitution, or of laying strong hand upon the colored element. I chose the latter.”[13] It is important to note that before the war, Lincoln and the Republicans were always advocating for the containment of slavery with the eventual voluntary abolition of slavery by the slave states. They were not advocating for the federal government to abolish slavery where it already existed. Here, Lincoln is looking to get the border states to adopt a gradual emancipation plan with compensation. When this offer is declined, he finally believed in the “indispensable necessity” of military emancipation.[14] So, slavery would have to end for military reasons.

Lincoln ended his letter using religion to further connect to his audience. It is interesting to note that this ending was not part of the original conversation with Hodges; it is possible that Lincoln did not find it vital in his conversation with the prominent men but saw its potential with the regular citizens. Lincoln wrote, “In telling this tale I attempt no compliment to my own sagacity. I claim not to have controlled events, but confess plainly that events have controlled me. Now, at the end of three years struggle the nation’s condition is not what either party, or any man devised, or expected. God alone can claim it.”[15] In closing in this manner, he pivoted the responsibility for his choices from himself to a “Divine purpose…at work.” [16] This is a similar theme to Lincoln’s Second Inaugural Address that he gave in March 1865 after winning reelection in November 1864. As Historian David Herbert Donald noted, “This comforting doctrine allowed the President to live with himself by shifting some of the responsibility for all the suffering.”[17] So, even if the reader did not trust Lincoln based on his personal beliefs, the reader could trust that Lincoln’s decision was in part guided by God.

Lincoln’s ultimate goal with this letter was to explain the evolution of his emancipation policy and convince the people of Kentucky in the process. Hodges wrote to Lincoln on April 22, after this public letter, saying, “It is with feelings of profound satisfaction I inform you, that… I have been receiving information of your steady gain upon the gratitude and confidence of the People of Kentucky.”[18] Yet, in the November election, Kentucky was one of only three states to vote for Democrat George McClellan.[19] However, this should not be viewed as a failure for Lincoln, as Kentuckians supported Lincoln more in 1864 than they had in 1860.[20] It is possible that his April 4, 1864, public letter to Albert Hodges convinced people to trust him in claiming the “indispensable necessity” of emancipation. More broadly the letter provided insight into Lincoln’s own understanding of the evolution of his emancipation policies.

[1] Ronald White, Lincoln’s Greatest Speech: The Second Inaugural, (New York: Simon and Schuster, 2006), 82, https://books.google.com/books?id=wtfLtP2LhCcC&printsec=frontcover&source=gbs_ge_summary_r&cad=0#v=onepage&q&f=false.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Douglas L. Wilson, “Lincoln’s Rhetoric,” Journal of the Abraham Lincoln Association, 34, 1, (2013), http://hdl.handle.net/2027/spo.2629860.0034.103.

[5] Abraham Lincoln to Albert G. Hodges, April 4, 1864, Washington, DC, in Roy P. Basler, ed., The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln (8 vols., New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1953), 7: 281-283, http://quod.lib.umich.edu/l/lincoln/.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Wilson, “Lincoln’s Rhetoric.”

[8] Abraham Lincoln to Albert G. Hodges, April 4, 1864.

[9] Wilson, “Lincoln’s Rhetoric.”

[10] Abraham Lincoln to Albert G. Hodges, April 4, 1864.

[11] Ibid.

[12] Ibid.

[13] Ibid.

[14] Ibid.

[15] Ibid.

[16] David Herbert Donald, Lincoln (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1995), 514-515, from: http://housedivided.dickinson.edu/sites/lincoln/letter-to-albert-hodges-april-4-1864/.

[17] Ibid.

[18] Albert G. Hodges to Abraham Lincoln, April 22, 1864, Letter, From Library of Congress, The Abraham Lincoln Papers.

http://memory.loc.gov/cgi-bin/query/r?ammem/mal:@field(DOCID+@lit(d3254000)) (accessed July 20, 2016).

[19] David Leip, 1864 Presidential General Election Results – Kentucky, U.S. Election Atlas, Accessed July 20, 2016, “http://uselectionatlas.org/RESULTS/state.php?f=0&fips=21&year=1864.

[20] “Kentucky’s Abraham Lincoln,” The Kentucky Historical Society, Accessed July 20, 2016, http://www.lrc.ky.gov/record/Moments09RS/web/Lincoln%20moments%2025.pdf.

While this difference can also be attributed to the mid-war political reality in Kentucky (where many Kentuckians were fighting for the Confederacy) and the fact that Kentucky was military occupied, some of the support might be tied to this public letter in which Lincoln explained his policies.

What happened in Kentucky after the Civil War ended?

For the answer, read: "How Kentucky Became a Confederate State" by Christopher Phillips