Lindsay Peterson, "Primary Documents Within the Context of the Antebellum Era and the Civil War," TimelineJS.

Lincoln's Emancipation Policies: Evolution or Change?

Was the Civil War fought to save the union or end slavery? Were Lincoln’s emancipation policies during the Civil War a natural evolution from his pre-war ideas on containment or was there a shift? Did Lincoln believe the war was fundamentally about union or freedom, or both? What did he mean by “union”? And what did “freedom” encompass? Historians differ in their answers to these questions based on their unique interpretations of the primary sources. Before we get started in trying to answer these questions for ourselves, we must examine Lincoln’s opinions before and during the Civil War in order to understand the primary and secondary sources for ourselves.

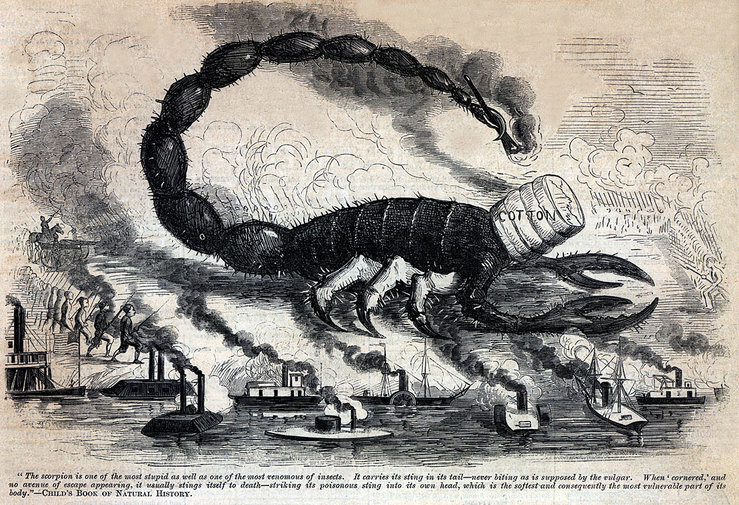

"The scorpion is one of the most stupid as well as venomous of insects. It carries its sting in its tail - never biting as is supposed by the vulgar. When 'cornered' and no avenue of escape appearing, it usually stings itself to death - striking its poisonous sting into its own head, which is the softest and consequently the most vulnerable part of its body."

Frank Leslie's Illustrated Newspaper, May 24, 1862, p. 96.

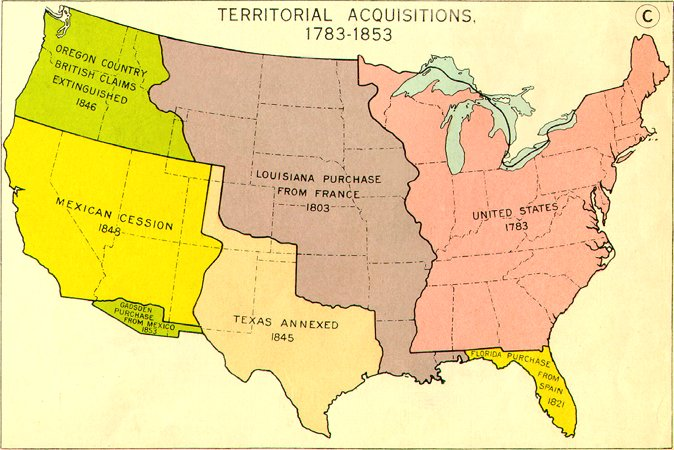

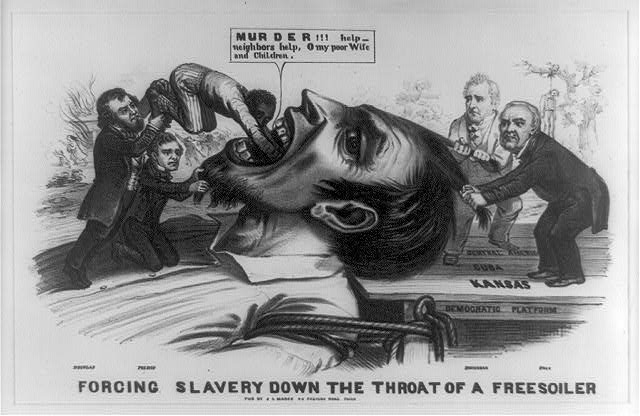

The Republican Party emerged in 1854, committed to a strategy of the containment of slavery. While they did not think that the Constitution condoned slavery nor believe that the Founding Fathers wanted the expansion of slavery, the new party recognized that the federal government did not have the power to abolish slavery where it already existed by overruling state laws. Hence, they focused on containing slavery more indirectly by regulating the areas where the federal government did have control – the ocean, the District of Columbia, and the western territories. The hope of the Republicans was that through keeping slavery from expanding, it would ultimately become extinct where it already existed. As James Oakes discussed in his book The Scorpion’s Sting: Antislavery and the Coming of the Civil War, the Republicans believed that the “scorpion,” the Southern slave states, would be surrounded by a “ring of fire,” the cordon of freedom, and eventually sting itself to death. In Oakes’ most recent book, Freedom National, he continued this analysis into the Civil War – arguing that Lincoln’s wartime policies reflected a belief that freedom should be a national phenomenon. Therefore, the Republicans were committed to freedom even before the war began and that commitment did not diminish during the conflict.

Lincoln stated his views on slavery as early as October 1845 in his letter to Williamson Durley. In this letter, Lincoln discussed the impending annexation of Texas. Lincoln was frustrated that Durley and others in New York voted for the Liberty Party, allowing Whig candidate Henry Clay to lose to the Democrat’s James Polk. Durley and others did not support Clay because he was a slave owner who believed in gradual emancipation. However, Lincoln tried to explain to Durley that Clay would have helped to contain slavery in regards to the Texas question. Lincoln wrote, “I hold it to be a paramount duty of us in the free states, due to the Union of the states, and perhaps to liberty itself…to let the slavery of the other states alone; while on the other hand, I hold it to be equally clear, that we should never knowingly lend ourselves directly or indirectly, to prevent that slavery from dying a natural death.”[1] Even before the Republican Party emerged, Lincoln stated his belief in the containment of slavery and his recognition that the federal government could not interfere with slavery in the states where it already existed.

NationalAtlas.gov, https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/c/c4/United-states-territorial-acquistions-midcentury.png

Throughout the antebellum era, the country debated the expansion of slavery – evidenced by the Compromise of 1850, the Kansas-Nebraska Act, the Supreme Court’s Dred Scott decision, and more. In the midst of the Lincoln-Douglas debates, Lincoln gave his “House Divided” Speech. In his speech to the Illinois Republicans, Lincoln shared his belief that slavery would reach its “ultimate extinction” through voluntary abolition by the southern states. Lincoln’s most remembered lines from the speech, “A house divided against itself cannot stand. I believe this government cannot endure, permanently half slave and half free” seemed to insinuate an impending crisis surrounding the future of slavery.[2] Historians may look to this speech to argue that the focus of the war for Lincoln was ending slavery.

Drawn by John L. Magee. Published in: American political prints, 1766-1876 / Bernard F. Reilly. Boston : G.K. Hall, 1991, entry 1856-8. http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.pnp/cph.3b38367

|

The Picture Collection of the New York Public Library, NYPL Digital Gallery

|

In the midst of his 1860 presidential election campaign Lincoln gave his Address at Cooper Union. Lincoln took this opportunity to reiterate his belief that slavery was evil and should not be extended. He also emphasized the ideas of the Founding Fathers on the subject of slavery, writing that the majority “certainly understood that no proper division of local from federal authority, nor any part of the Constitution, forbade the Federal Government to control slavery in the federal territories.”[3] This quote fits with the Republican Party commitment to containment. However, following the polarizing nature of John Brown’s raid on Harper’s Ferry, Lincoln was sure to distance himself from Brown’s violent means.

|

|

After Lincoln won the 1860 presidential election, Lincoln focused on the idea of the union in his “First Inaugural Address.” Historians who argue that the Civil War was first and foremost about maintaining the union, with freedom being either secondary or not a goal, focus on this speech, as there is a focus on union and no direct discussion of slavery. Gary Gallagher, in The Union War, argued that the Civil War was fought for the preservation of the Union and argues that those who believe the war was for freedom apply their own preconceived notions to the historical record (the idea of presentism). In this speech Lincoln repeatedly emphasized the “perpetual” nature of the Union and stated, “Plainly, the central idea of secession, is the essence of anarchy.”[4] In this way, Lincoln could be interpreted to be setting the stage for what conflict would be about – maintaining the union. However, historians who focus on the Civil War being a war for freedom note that Southerners understood the context of this address and that even if Lincoln did not recognize his anti-slavery opinions in this speech, he had previously made them public. With the firing on Fort Sumter six weeks later, the Civil War began – would it be a war primarily to save the union or free the slaves?

|

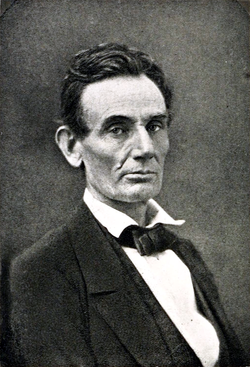

Frontispiece of Schurz, Carl (1891) Abraham Lincoln: An Essay (5th ed.), Cambridge, Massachusetts: Houghton, Mifflin & Co.

|

|

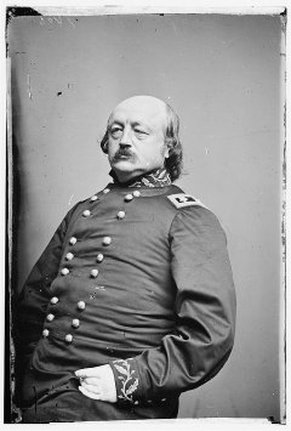

Major General Benjamin Butler (Library of Congress)

|

From early in the war Lincoln had to deal with the issue of emancipation, as three slaves escaped to Union lines at Fort Monroe in May 23, 1861, to see how General Butler would respond. Butler refused to return the troops because he felt no obligation to return them under the Fugutive Slave Act, as the Confederacy was claiming to be a separate nation, and he also believed he had to keep them as a military necessity; if Butler returned the slaves, he would be providing the Confederacy with a labor force. Butler recognized that he could use the runaway slaves to help the Union war effort. After these individuals helped support the Union, many believed it would be impossible to send them back into slavery after the war. This became the basis of the argument for the military necessity of emancipation.

During the war, Lincoln did not support emancipation until he believed that it was a military necessity. In the summer of 1862, Congress passed the Second Confiscation Act which gave the president the power to label slaves as contraband and free them. The First Confiscation Act, passed by Congress in August 1861, allowed Union army officials to seize slaves employed by the Confederate army but did not include provisions for freedom. The Second Confiscation Act clarified this point, emphasizing that Confederate slaves were “captives of war” who were to be “forever free.” Lincoln did not believe that this act was completely constitutional and did not apply to all of the slaves, so he felt the need to follow up with his own emancipatory action – the Emancipation Proclamation. |

The Second Confiscation Act only related to areas under rebellion and Lincoln recognized that slavery also still existed within some areas in the Union – in the border states and the District of Columbia. Lincoln therefore worked with Congress to abolish slavery in the District of Columbia in 1862. It is in the spring of 1862 that Lincoln warned the border states that if they didn’t abolish slavery on their own, the institution would be destroyed by the war. By 1862, Lincoln’s two distinct policies, state abolition and military emancipation, were converging. Oakes argues that Lincoln used military emancipation to create the “cordon of freedom.”

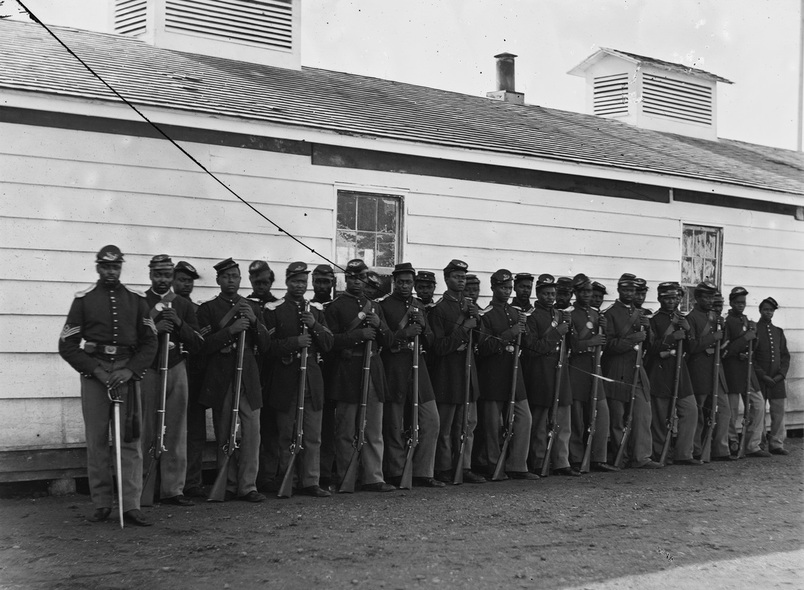

The First Draft of the Emancipation Proclamation built upon the Second Confiscation Act by allowing for enticement of slaves into Union lines and for enrollment of black soldiers into the Union Army. The opportunity to enroll in the Union Army led to the freedom of many slaves from border states, the areas exempted from emancipation under the Emancipation Proclamation. It is worth noting that by 1864, 100,000 African Americans were fighting for the Union – making up over one-fifth of the army. Lincoln read this draft to his Cabinet and it remained private until he announced his intention for emancipation in September. Prior to this proclamation, the freeing of slaves had been all about treason – individual, disloyal slave owners could lose their slaves. However, as Commander-in-Chief, Lincoln framed emancipation as a military necessity in which he would free the slaves in all areas in rebellion, even if their masters were loyal. The idea of military emancipation was not a new idea, but one used throughout history in order to end wars.

Courtesy of U.S. Senate

|

One month after he had drafted and delivered his First Draft of the Emancipation Proclamation to his Cabinet, Lincoln wrote an angered and critical Horace Greeley. Greeley was frustrated that Lincoln was not enforcing the emancipating power he was given under the Second Confiscation Act. When Lincoln wrote this letter, he had already decided to issue the Emancipation Proclamation. However, Lincoln recognized that as much as Greeley would be thrilled to hear the news, his opponents would be worried and Lincoln was afraid of possible fracturing within the Union – especially in regards to the Unionist border states where slavery still existed. Lincoln wrote, “My paramount object in this struggle is to save the Union, and is not either to save or to destroy slavery. If I could save the Union without freeing any slave I would do it, and if I could save it by freeing all the slaves I would do it; and if I could save it by freeing some and leaving others I would also do it.”[5] Taken out of the context of the First Draft of the Emancipation Proclamation and the official Proclamation, Lincoln’s letter, seemed to argue a war for union. However, while Lincoln’s rhetoric to Greeley is all about union, he had already made up his mind about emancipation.

|

Mathew Brady Photographs of Civil War-Era Personalities and Scenes, National Archives and Records Administration

|

In September, Lincoln named January 1, 1863, as the official date emancipation would begin – when he issued the Emancipation Proclamation. Because Lincoln recognized that the emancipation of slaves was part of his military powers that would end when the war ended, he strove to ultimately solidify the freedom through the ratification of the 13th Amendment to the Constitution. However, Lincoln did not free all of the slaves with a stroke of the pen on January 1, 1863. Some slaves had already been freed by occupying Union forces and in other areas it would take time to enforce this proclamation. Eric Foner, in The Fiery Trial: Abraham Lincoln and American Slavery, describes the process by which Lincoln came to accept emancipation and his struggle to recognize equality for African Americans. This begs the question, what did “freedom” encompass for Lincoln?

Company E, 4th US Colored Troops at Fort Lincoln, November 17, 1865 (from Library of Congress)

As Lincoln noted in his 1864 Letter to Albert Hodges, he was initially resistant to attempts by his generals to emancipate slaves. In this letter, Lincoln repeatedly referred to the distinction between his private views and public duties and noted that his actions as President were not driven by his individual opinions. However, Lincoln wrote, “I felt that measures, otherwise unconstitutional, might become lawful, by becoming indispensable to the preservation of the constitution, through the preservation of the nation.”[6] Historians could use this letter to argue that Lincoln’s focus throughout the entire war was preserving the union first and foremost.

Scholars examine Lincoln’s emancipation policies during the Civil War and have drawn different conclusions about the relationship between the war for the union and the war for freedom. James Oakes believes that all along it was a war for freedom that also saved the union. Gary Gallagher and James McPherson both conclude that it began as a war for union – with Gallagher believing that the war also extended to freedom and McPherson determining that it became a war for freedom. Eric Foner added scholarship on Lincoln’s complicated relationship with slavery and African Americans, in particular his hesitancy to acknowledge their full equality as citizens. These historians are all examining the same primary sources but interpret them in different ways to support their claims. It is now your turn to be the historian and draw your own conclusions based on the sources found on this website.

So, at what point does the Civil War turn from a war for union to a war for freedom? When and why does Lincoln shift from the idea of containment to widespread emancipation? Is there a shift, or did Lincoln's emancipation policy evolve naturally from his previous ideas?

[1] Abraham Lincoln to Williamson Durley, Springfield, Illinois, October 3, 1845 in Roy P. Basler, ed., The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln (8 vols., New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1953), 1: 347-348, http://quod.lib.umich.edu/l/lincoln/.

[2] "A House Divided'': Speech at Springfield, Illinois in Roy P. Basler, ed., The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln (8 vols., New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1953), 2: 461-469, http://quod.lib.umich.edu/l/lincoln/.

[3] Address at Cooper Institute, New York City in Roy P. Basler, ed., The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln (8 vols., New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1953), 3: 522-550, http://quod.lib.umich.edu/l/lincoln/.

[4] First Inaugural Address---Final Text, March 6, 1861 in Roy P. Basler, ed., The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln (8 vols., New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1953), 4: 262-274, http://quod.lib.umich.edu/l/lincoln/.

[5] House Divided, Letter to Horace Greeley (August 22, 1862), July 27, 2016, http://housedivided.dickinson.edu/sites/lincoln/letter-to-horace-greeley-august-22-1862/.

[6] Abraham Lincoln to Albert G. Hodges, April 4, 1864, Washington, DC, in Roy P. Basler, ed., The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln (8 vols., New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1953), 7: 281-283, http://quod.lib.umich.edu/l/lincoln/.

[1] Abraham Lincoln to Williamson Durley, Springfield, Illinois, October 3, 1845 in Roy P. Basler, ed., The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln (8 vols., New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1953), 1: 347-348, http://quod.lib.umich.edu/l/lincoln/.

[2] "A House Divided'': Speech at Springfield, Illinois in Roy P. Basler, ed., The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln (8 vols., New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1953), 2: 461-469, http://quod.lib.umich.edu/l/lincoln/.

[3] Address at Cooper Institute, New York City in Roy P. Basler, ed., The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln (8 vols., New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1953), 3: 522-550, http://quod.lib.umich.edu/l/lincoln/.

[4] First Inaugural Address---Final Text, March 6, 1861 in Roy P. Basler, ed., The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln (8 vols., New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1953), 4: 262-274, http://quod.lib.umich.edu/l/lincoln/.

[5] House Divided, Letter to Horace Greeley (August 22, 1862), July 27, 2016, http://housedivided.dickinson.edu/sites/lincoln/letter-to-horace-greeley-august-22-1862/.

[6] Abraham Lincoln to Albert G. Hodges, April 4, 1864, Washington, DC, in Roy P. Basler, ed., The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln (8 vols., New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1953), 7: 281-283, http://quod.lib.umich.edu/l/lincoln/.